Journalists take note, people lie: Elizabeth Toledo tells how journalists and news organizations can avoid falling victim to ambush videos intended to discredit or humiliate them.

Category Archives: Accuracy

Newsroom Ethics Panel

Carol Marin, Chicago journalist

By Casey Bukro

“Fake news began with the cavemen,” asserts Carol Marin, a leading Chicago television and print journalist.

A caveman returned to his cave, telling heroic stories about his exploits. “The demons he killed were enormous,” Marin assured an audience gathered to hear a newsroom ethics panel featuring some of the Chicago region’s best-known journalists. “It has always been a presence in our lives.”

The topic was “Fake News” versus “Real News.” The place was the WGN-TV studie in Chicago.

“Facts matter,” said Margaret Holt, the Chicago Tribune’s standards editor. “It all begins with facts.”

Holt recited a famous dictate of Chicago journalism: “If your mother says she loves you, check it out.” Take nothing for granted and check out everything.

“The job of journalism is to get facts, get facts clear,” said Holt.

Don Moseley, a political and investigative television producer offered this: “Specificity, for people who watch and read. Specificity.”

Moseley is co-director with Marin of DePaul University’s Center for Journalism Integrity and Excellence.

Marsha Bartel, WGN-TV investigative producer, believes “people have become too passive. You’ve got to do work on your own. I urge everybody to become better consumers.”

Maggie Bowman, a documentary file producer for Kartemquin Educational Films in Chicago, said audiences weigh information given to them.

“It’s up to us as storytellers to be transparent, like who funds us,” said Bowman. Resita Cox, a City Bureau reporter, agreed: “Explain how you got to where you got to.” City Bureau is a nonprofit civic journalism lab in Chicago.

Holt added: “Also, ask what’s the voice that is missing. Have more voices. Look at who is missing.”

This was the next question: How do you determine the reliability of sources, and whether to use anonymous sources?

A two-source rule is helpful, said Marin. “We spend a lot of sleepless nights looking at the pieces of the story,” including the motives of sources.

Moseley: “When you use anonymous sources, you vet them, their background and the foundation of their knowledge.”

Bartel: Most sources have a motive. “I take the sources as a lead” and look for documents to verify what the source said. “Work it and work it and keep adding pieces of information. I really try not to use anonymous sources any more, unless there is no other option.”

Moseley: “Think carefully before you use them.”

Next question was how social media complicates the lives of journalists.

Social media can help develop a story, said Cox, but “is the person telling the truth? Is this a story? You have to go the extra step and verify sources.”

Next question, what is a conflict of interest?

Holt pointed out that the late Jerome Holtzman, a former Chicago Tribune sports writer, wrote a book entitled, “No Cheering in the Press Box.” It warned sports writers to avoid taking sides in reporting sporting events, but Holt said that advice applies to all journalists.

“There has to be personal separation,” said Holt. “You cannot separate yourself from your social media presence. You have to be careful about how you present yourself in the professional world.”

Marin added: “We don’t take a side, we don’t belong to anyone’s club. It’s very hard to impress that on young journalists. We’re not there to support, but to present the facts.”

On the issue of copyright and fair use, Bowman said “fair use is a way of finding the balance in copyright material.” It’s difficult, she said, to use copyright material without paying exorbitant fees. She typically uses seconds or minutes of television clips for historical content, for example.

“As users of copyright material we continually defend our right to use it,” she said. Fair Use laws, she said, allows “free expression in our democracy,” adding “we can’t make things completely objective, but we can be transparent.”

For a source on fair use, free speech and intellectual property, Bowman suggested going to the Center for Media and Social Impact at cmsimpact.org. It is based in Washington, D.C.

On television, Marin said journalists often fail to explain the difference between news and analysis, a point of view. “In a lot of ways we fail.”

The next question wondered about a reporter’s rights in public and private settings, considering that journalists sometimes are told to leave the premises.

“If someone asks you to leave their house,” answered Cox, “you have to leave the house. But the sidewalk is public. Trespassing is a big thing. You have to figure your way around it.”

When covering government, said Marin, officials will try to set the rules.

“None of them really like the press,” said Marin. “But it is our job to cover them whether they like it or not. They are public officials.”

Holt added: “Arm yourself with education before you get into this. Army yourself. There is all kinds of training. There are things you can do even before you get into this position. We will fight. It’s incumbent on us to know what we have a right to.”

Bartel pointed to an alarming change in attitudes toward reporters since she first started covering presidential national conventions.

At the 2016 Republican National Convention in Cleveland, she said, “we were shouted at, called liberal media. I’ve never seen anything like that. It’s a very different atmosphere and felt like this was not a safe place to be.

“In this environment, you need to defend yourself and speak out” because there is a tendency to attack reporters.

On the issue of making mistakes, Holt said, “we all make mistakes and own your mistakes. What’s the point of making mistakes if you don’t learn from it? The people who make the most mistakes have the most challenging jobs. If you make mistakes over and over again, that is on you. Do the best you can in the time available. You build your credibility day by day.”

Moseley recalled that in speaking to a class, Holt pointed out that baseball players who sit on the bench during a game make no mistakes.

Race relations complicate the life of a journalist, Cox pointed out.

“I feel like we’re at war with each other,” she said. “I’m a woman of color and reporting in an era of Trump.” There are stories that don’t tell both sides, she said.

Marin said she opposes the idea of expecting African American reporters to cover African American issues. She would object to being identified as a white reporter with Swedish heritage, she said.

“We lose reporters who see nuances” by attempting to pigeon hole them according to ethnicity, said Marin.

Bartel added: “I think we are giving too much voice to the KKK. When I started I thought everything was black and white. Now it’s all shades of gray. The world is not right or wrong, black or white.”

In a similar vein, Cox said: “There are stories that are outright wrong and we don’t have to give a platform to those people.”

Holt said journalism often is “driven by white, older men. It’s difficult if you are a young reporter to balance this stuff. Part of what you bring to the job is you come from a different place. That is a valuable voice. Young people see the world differently from those with a more traditional view.”

The Trust Project

The Trust Project: Laura Hazard Owen says the project is a global effort to provide clarity on news organization ethics and standards and how journalists do their work.

Beauty Norms

Photographer apologizes for changing an actress’s hair style in a magazine cover photo, calling it “an unbelievably damaging and hurtful act.” Actress Lupito Nyong’o complained it was an attempt to make her fit “Eurocentric” beauty norms.

Publish unverified documents? Consider these ethical questions

By David Craig

BuzzFeed’s decision last week to publish a 35-page dossier containing allegations about President-elect Donald Trump’s relationships with Russia has prompted a great deal of discussion among journalists and journalism organizations about the ethics of the decision.

A number of those weighing in – such Washington Post media columnist Margaret Sullivan and Poynter Institute for Media Studies ethicist Kelly McBride – have argued that BuzzFeed was out of line for publishing unverified information. But some – including Watergate reporter and now CNN analyst Carl Bernstein and Columbia Journalism Review managing editor Vanessa M. Gezari – supported the decision.

I have been thinking beyond this situation to similar ones that may arise in the future and the ethical questions involved.

Below is a list of questions I’m suggesting to help in thinking through the ethical issues in these situations. I have grouped the questions under the headings of the principles of the Society of Professional Journalists ethics code, as well as other considerations – public relevance and journalistic purpose – that relate to the mission of journalism.

In writing these questions, I’m inspired by some lists that Poynter has done to help journalists in other areas of ethical decision-making such as going off the record and, recently, using Facebook Live. Two co-authors and I also raised some of these issues in a question list in an academic study on data journalism.

I welcome any comments from readers on how these questions might be used or revised.

Questions to consider in deciding on whether and how to publish unverified documents involving public officials:

Public relevance and journalistic purpose

Have the documents been discussed or used in any official settings (e.g. intelligence briefings, committee hearings)? Have they otherwise been discussed on the record by any public officials?

Is there a compelling reason for the public to know about the information in the documents?

Seeking truth and reporting it

Have you or others tried to verify the information? Where verification has been possible for specific pieces of information, has the information proved to be true?

Are the sources of the documents reliable? Why or why not?

Acting independently

Is your decision to publish based on your own independent judgment of the ethics of publishing or on competitive pressures or other considerations?

Minimizing harm

If the documents contain sensitive allegations, what potential harms could result if you release the documents in their entirety or publish those details and they prove to be false or impossible to verify?

If potential harm is a valid concern if you release the documents in their entirety or report details such as these, how could you minimize harm (e.g. redacting some details, summarizing)?

Being accountable and transparent

Are you explaining the process you used in your decision-making including any conflicting ethical considerations and the ethical reasons for making the decision you did?

Are you explaining any efforts you made to verify the content of the documents and the outcome of those efforts?

By thinking through these questions, journalists can uphold the importance of verification while also considering when and how to report on unverified documents there may be a compelling reason for the public to see.

Daley News: Preserving Disorder in Trump’s Washington

By Casey Bukro

Powerful men often have a way with words, although not always in the way we might expect.

Mayor Richard J. Daley of Chicago was famous for malapropisms, often saying the opposite of what he meant. He was Chicago’s powerful mayor for 21 years, and an example for journalists taking measure of Donald J. Trump.

Daley was the undisputed Democratic kingmaker in Illinois and beyond until his death in 1976, both feared and respected. Daley was a force in John F. Kennedy’s 1960 presidential victory, leaving lingering hints of vote fraud. A dressing down by Daley could leave his underlings in pools of sweat.

But his speech was sometimes tangled and mangled, often while he was agitated or angry. Such as the time he was talking about the battle being waged by police against street violence during the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

“Gentlemen, get the thing straight once and for all,” the mayor said. “The policeman isn’t there to create disorder; the policeman is there to preserve disorder.”

Continue reading Daley News: Preserving Disorder in Trump’s Washington

Fake News Trumps True News

By Casey Bukro

Fake news might have proved more interesting to readers than the factual stuff.

This sobering thought has churned angst over whether social-media falsehoods contributed to Donald Trump’s presidential victory, not to mention whether the upset win could have been foreseen.

News consumers tend to believe reports that support their personal beliefs — an effect that psychologists call confirmation bias. People like to believe they’re right. In the election run-up, they clicked their way across the internet to prove it.

As President-elect Trump selects the people who’ll help him govern, observers are picking through the rubble trying to understand the forces behind a Republican victory. Here our concern is news-media accuracy and ethics.

Let’s start with something basic. What is fake news?

“Pure fiction,” says Jackie Spinner, assistant professor of journalism at Columbia College Chicago, appearing on WTTW-Channel 11 in Chicago in a “Chicago Tonight” program devoted to separating fact from fiction in internet news feeds.

“It’s something made up,” adds Spinner. “It’s fake.”

But as the WTTW program points out, “fake news is on the rise, and it’s real news.” Some false reports, such as campaign endorsements from Pope Francis, survived many a news cycle.

Continue reading Fake News Trumps True News

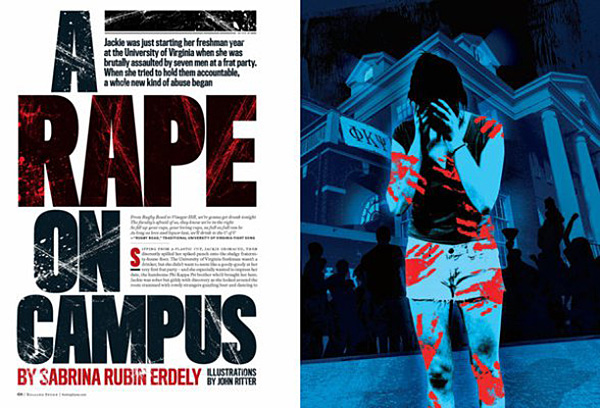

Rolling Stone In the Penalty Phase of a Faulty Rape Story

By Casey Bukro

Rolling Stone retracted its 2014 story about an alleged gang rape in a University of Virginia fraternity house after admitting post-publication doubts about the story’s accuracy. You might wonder what a blunder like that might cost a publication, and now we know.

The magazine was hammered by lawsuits. In November 2016, a federal court jury in Charlottesville, Va., awarded $3 million in damages to a former U.Va. associate dean, Nicole Eramo. The jury found that the Rolling Stone article damaged her reputation by reporting she was indifferent to allegations of a gang rape on campus. Eramo oversaw sexual violence cases at U.Va. at the time the article was published.

The jury concluded that the Rolling Stone reporter, Sabrina Rubin Erdely, was responsible for defamation with “actual malice,” which usually means a reckless disregard for the truth.

Continue reading Rolling Stone In the Penalty Phase of a Faulty Rape Story

Do Short Attention Spans Lead the News?

By Casey Bukro

The public’s shifting attention has implications across the media landscape, from CBS’ plans to sell its historic radio division to the expanding influence of topical comedy on TV and the internet.

Radio historian Frank Absher appeared on NPR’s “All Things Considered” to talk about the heyday of CBS radio. The broadcast described CBS as one of the first networks to truly realize the power of news and develop its uses. Established in 1928, the network owns 117 stations and has an illustrious news-breaking history.

Voices were key to that development—the calm, measured and authoritative voices of correspondents like Edward R. Murrow and Lowell Thomas.

What was the state of broadcast journalism when CBS started? “There wasn’t any,” said Absher, a member of the Radio Preservation Task Force and the St. Louis Media History Foundation. “Broadcast journalism did not exist, not even as a concept. In fact, the early, early radio stations would simply grab a newspaper because a lot of them were owned by newspapers. And they would read stories on the air out of today’s edition.”

Ironically, John Oliver, host of HBO’s “Last Week Tonight,” argues that much of today’s TV news still depends on what journalists find in daily newspapers. But back to Asher’s perspective.

Times Public Editor Blasts Sneak Interview

By Casey Bukro

Ambush interviews usually are not the way journalists conduct business. Seasoned professionals identify themselves as journalists and tell sources they intend to quote them, or ask permission to quote them. They make clear that remarks are “on the record.”

That’s the way it’s usually done. Ethics AdviceLine for Journalists occasionally get calls or inquiries, usually from young reporters, who don’t know that.

In 2012, a reporter doing an article on a controversial homeless shelter in New York asked: “Would it be unethical to call and not disclose that I am press?”

The answer from Hugh Miller, an AdviceLine consultant, was short and sweet: “Don’t. It would be unethical.”

Implicit in this exchange are questions of candor, disclosure and transparency. They raise the question of getting information under false pretenses.