Bill Green set the standard for ombudsmen while investigating the Janet Cooke hoax at the Washington Post. (Post photo).

By Casey Bukro

Bill Green, an ombudsman’s ombudsman, was not even sure what the job entailed when he was called on unexpectedly to unravel one of journalism’s most famous ethical failures.

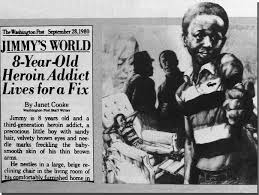

Green was only weeks into the job as Washington Post ombudsman on Sept. 28, 1980, when the Post published “Jimmy’s World,” the story of an 8-year-old heroin addict with “needle marks freckling the baby-smooth skin of his thin brown arms.”

So compelling and detailed, the front-page story written by 26-year-old reporter Janet Cooke won the Pulitzer Prize for feature writing on April 13, 1981.

Almost immediately the story about the unnamed boy, and Cooke’s background that appeared when the prize was announced, started falling apart.

The story that followed is especially notable for two reasons. One is that falsehoods often fail sooner or later. The other is that Green, an editor of small-town newspapers who took a year’s sabbatical from Duke University to serve as the Post’s reader advocate, wrote a blistering report on the Post’s editorial lapses that is a model of journalism accountability. It set the standard for ombudsmen.

The nine-part report, starting on the front page and covering four full inside pages, showed the Post’s willingness to confront its flaws and admit them publicly.

Many media outlets reported Green’s recent death, including the New York Times and the Washington Post, and prompted descriptions of the Janet Cooke episode here, here and here. They are good lessons for young journalists who might think that deceit is a way to get ahead in a very competitive business.

Cooke was a young, attractive, talented African-American woman. Her elegant feature-writing style captivated editors eager to promote women and minorities.

Her “Jimmy’s World” story “was debunked the day after it won a Pulitzer Prize,” said the New York Times.

The first red flag went up when Vassar College officials called the Post executive editor, the late Benjamin Bradlee, to deny that Cooke had graduate magna cum laude, as she claimed to the Pulitzer board. Actually, she left there after her freshman year.

At the same time, the Associated Press called the Post to report that AP staffers in Ohio learned that Cooke had not received a masters’s degree from the University of Toledo. She had a bachelor’s degree.

“You’ve got 24 hours to prove the ‘Jimmy’ story is true,” Bradlee told Cooke, after calling her and several editors to his office, according to Green.

Cooke admitted the biographical details were false but insisted the “Jimmy” story was true. It described an 8-year-old addicted to heroin since he was 5, when his mother’s live-in boyfriend first allowed the child to sniff some heroin. The boyfriend, said the story, was a heroin dealer, and that Jimmy’s mother and grandmother also were heroin addicts.

“He nestles in a large, beige reclining chair in the living room of his comfortably furnished home in Southeast Washington,” said Cooke’s story. “There is an almost cherubic expression on his small, round face as he talks about life — clothes, money, the Baltimore Orioles and Heroin.”

The end of the article described the boyfriend injecting Jimmy with heroin and saying, “pretty soon, man, you got to learn to do this for yourself.”

Cooke told her editors before the article was published that she promised Jimmy and his mother anonymity. She also said the mother’s boyfriend threatened her life if authorities found them.

Under orders to find and identify Jimmy, Cooke and a Post editor drove to the Washington neighborhood where Cooke insisted Jimmy lived. But she could not find his house.

The nine-part report, starting on the front page and covering four full inside pages, showed the Post’s willingness to confront its flaws and admit them publicly.

At the Post, editors examined Cooke’s notes and listened to recorded interviews with drug experts and social workers. There were no notes or tapes about Jimmy and his family.

Returning to the Post that night, Cooke continued to insist her story was true during a meeting with several editors. They began having doubts.

The next morning, Cooke confessed that Jimmy did not exist and that he was a composite of several young drug users. It was an artful hoax in which she not only invented the story about Jimmy, she also concocted a story about herself with a faked resume.

Upon learning the truth, Bradlee said: “It is a tragedy that someone as talented and promising as Janet Cooke, with everything going for her, felt that she had to falsify the facts. The credibility of a newspaper is its most precious asset, and it depends almost entirely on the integrity of reporters.

“When that integrity is questioned and found wanting, the wounds are grievous, and there is nothing to do but come clean with our readers, apologize to the Advisory Board of the Pulitzer Prizes and begin immediately on the uphill task of regaining our credibility. This we are doing.”

An editorial offered a public apology. The Pulitzer board at the Columbia School of Journalism withdrew Cooke’s prize and gave it to the runner-up.

In a statement, Cooke said the article “was a serious misrepresentation which I deeply regret. I apologize to my newspaper, my profession, the Pulitzer board and all seekers of the truth.”

‘When that integrity is questioned and found wanting, the wounds are grievous.’

At this point, Bradlee turned to Green to investigate and write a report about the Cooke debacle.

“His tenure became notable when he wrote one of the most damning and thorough critiques of malfeasance in modern journalism, revealing the depth of deception by Cooke and the carelessness of her editors that led to one of the most humiliating episodes in the Post’s history,” the Post reported at Green’s death.

Bradlee had created the ombudsman position in 1970, making the Post the first major paper to employ an independent in-house critic.

“When I discussed taking this job with the Post, I asked what the point of an ombudsman was,” Green told the Duke University alumni magazine in 2003. Green was Duke’s director of university relations and taught news writing when he decided to take a year off and take the Post’s ombudsman offer.

It turned into one of the most demanding and high-profile experiences of his life.

Green wrote a 18,000-word account of what went wrong at the Post in Cooke’s reporting, the paper’s editing and failure of oversight.

“It was an intense, exhausting experience and not all that pleasant because the Washington Post is one of our great newspapers that had made a terrible mistake,” Green told a North Carolina newspaper. “It was a dark day in journalism.”

Green conducted about 40 interviews, then using a typewriter, the basic tool of the trade at the time, he typed “for 28 uninterrupted hours,” he said.

“There’s enough blame to go around,” Green wrote. “Ben Bradlee, the executive editor was wrong, and Howard Simons, the managing editor, was wrong. Beginning, of course, with Janet Cooke, everybody who touched this journalistic felony – or should have touched it and didn’t – was wrong.”

Green called it “a complete systems failure, and there’s no excuse for it. These are brilliant people. The Post newsroom runs over with high-caliber talent and skills that weren’t employed.” Not a single Post supervisor had asked Cooke to identify Jimmy, even confidentially.

Green gave a detailed, embarrassing report about a newsroom where a drive for impact overrode several experienced journalists’ doubts that Jimmy actually existed.

Not a single Post supervisor had asked Cooke to identify Jimmy, even confidentially.

“There is no Jimmy and no family,” Cooke said, according to Green’s investigation. “It was a fabrication. I did so much work on it, but it’s a composite.” Once a rising star at the paper, Cooke resigned.

In his obituary, Bradlee was described as an editor who rarely dug into the details of an issue himself, leaving that to the people he hired. But Green recalled that Bradlee came to his Post office early one Saturday to read his report the day before the Post published it.

As Green recalled it, Bradlee finished reading the report and “came charging out when it was over. And he said in that marvelous, hoarse voice of his, ‘Bill Green, you ungrateful sonofabitch, I salute you.’ That was a high compliment, obviously.” Bradlee was known for the salty language he picked up during service in the Navy.

In his 1995 autobiography, Bradlee praised Green for accomplishing “an incredibly difficult task: a no-hold-barred, meticulously reported account of what went wrong – 18,000 words spread over the front page and four full pages inside.” He praised Green as “one wise and fair sumbitch, as the locals say.”

“One conclusion I reached,” Bradlee said, “is you cannot legislate, you cannot make a rule that is going to prevent, preserve you, save you from a pathological liar.” Years later, asked if the Cooke affair still rankled him, he replied: “In my soul.” It is a response that anyone who cares deeply about the future of journalism would give.

In Green’s obituary, Matt Schudel and Emily Langer describe the report “an inside view of how journalism works — and how it sometimes fails.” It is a model of ombudsmanship because it pulls no punches and offers recommendations to fix the problems.

“Race may have played some role,” Green wrote, “but professional pride and human decency were deeply involved in this story, and that has not a diddle to do with race.” Given its competitive nature, he added, the Post “may very well have unwittingly encouraged her success and thereby hastened her failure.”

In there aftermath of returning the Pulitzer Prize, the Post reported that editors across the nation “waded into the most far-ranging debate in a decade on how newspapers do their jobs,” calling the Cooke episode “unparalleled in modern journalistic history.”

The Chicago Tribune’s managing editor at the time, William Jones, said, “what this one person did has a hell of a lot of potential to create problems for all of us when it comes to source information.”

In 1982, Cooke appeared on “The Phil Donahue Show” and said she was sorry for what she did at the Post, but that the high-pressure working environment at the paper forced her to make an unwise decision. Sources had hinted of the existence of a boy such as Jimmy, she said. Unable to find him, she eventually created a story about him to satisfy her editors.

Ironically, Bob Woodward of Watergate fame was the Post’s assistant managing editor at the time, and personally submitted the story for the Pulitzer Prize. After it proved to be a fake, Woodward was quoted as saying: “I believed it, we published it.”

He reportedly also said, “It is a brilliant story – fake and fraud that it is.” His defense of Cooke’s work brings to mind an aphorism of jaded Chicago journalists: “Don’t let the facts get in the way of a good story.”

In a set of 15 recommendations for the newspaper, Green concluded: “If the reporter can’t support the integrity of his or her story by revealing the name to his or her editor, the story shouldn’t be published. And if that safeguard prevents some news stories from appearing, so be it.”

Naming names is the standard, or should be.

That should be the standard, and it is at some newspapers across the country. However, the New York Times recently adopted new standards against the use of unnamed sources at the insistence of its own reader representative because “in rare cases” stories using this device proved false.

The Cooke hoax resonates decades later for young minority reporters who believe their work is challenged unfairly. ”

Jimmy’s World” has become a case study in journalism ethics classes. It was featured in “The Hoax Project.” The Washington Post faced up to the potential credibility catastrophe.

It would be difficult to pinpoint a Bill Green ombudsman legacy in journalism, or to gauge the lasting impact of his work, other than to say he created the gold standard for fearlessly describing a newsroom’s troubles in an even-handed and insightful way. And it was colorful and interesting reading. Someone should name an ombudsman award after him.

The Society of Professional Journalists ethics code suggests: “Acknowledge mistakes and correct them promptly and prominently.” It also says journalists should “expose unethical conduct in journalism, including within their organizations.”

Post editors would have benefited from a lesson rookie reporters learned at the City News Bureau of Chicago, once described as the Devil’s Island of journalism. Editors there insisted: “If your mother says she loves you, check it out.”

Edited by Stephen Rynkiewicz. Comment below in the “Leave a Reply” box. For advice from our ethics advisers, submit a question.